Many women struggle with the after effects of childbirth and the overwhelm of having a little human who relies on them 24/7. The term ‘post-natal depletion’ (I first heard from my clinical psychologist friend Karen) accurately describes the nutrient state of a new mum, and whilst some women may experience depressive symptoms because of this, others feel general weariness and fatigue that is an expected part of being a mum. I recently listened to a podcast with the amazing Lily Nichols (well known for her work on gestational diabetes and diet) and her thoughts on the role of nutrients and if there is anything that can be done to mitigate these symptoms or help the recovery process, pre and post birth.

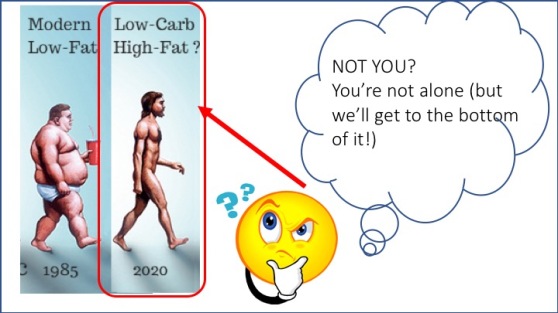

From a fitness perspective, if we consider the evolutionary picture, there is a definite mismatch between the activities of adults then compared to now. In activities of daily living there was a lot more squatting, lifting, lunging and pulling as part of gathering food and providing shelter. This made for a much stronger pelvic floor and core muscles than we have now. The strength and muscular fitness of the mother during pregnancy can really influence their recovery period post-birth. In addition, one of the main roles of the elders at the time of late pregnancy and childbirth is believed to have been to gather the additional calories required by the childbearing women, as it is difficult to obtain that amount of dietary energy. There was an enforced rest period post birth to help with recovery and bonding of child and mother, and this isn’t a focus in modern day life, where there seems to be real pressure to get back up on your feet after a few days and get going. From a food standpoint, the overwhelming and all-encompassing burden of being a mother to a new-born (first or third time around) makes it challenging to prioritise the nutritious meals required.

Childbirth is extremely energy demanding, whether you have a physiological (vaginal) birth or whether you have a caesarean section (c-section). For some, the double whammy of the intention to have a natural birth but, after 40 hours of labour, be whipped into surgery for a c-section likely even more so. The emotional and physical trauma relating to all of the above scenarios should not be understated, however while guidelines exist during pregnancy for nutrition, there are no real guidelines in place for postpartum recovery. The nutrient requirements of growing another human, plus the demands of labour leaves a woman in a very real depleted state, from a caloric perspective and from a nutrient perspective. It is therefore no wonder that women experience exhaustion and a depressive mood post childbirth. Furthermore, upregulation of protein turnover occurs post birth (both via c-section and vaginal) to help repair and heal tissue, and as a result of increased inflammation. This will certainly increase the requirements for protein and the amino acids responsible for musculoskeletal health.

And what about carbohydrate calories? It appears to be individual as to the requirement for most women. If someone develops gestational diabetes during pregnancy and has been limiting their carbohydrate intake, Lily suggests it is prudent to continue this lower carbohydrate approach post pregnancy for 6-12 weeks and ideally self-monitor their blood glucose responses to meals with a glucometer to assess if their levels has reduced to normal range. There is no optimal intake amount for carbohydrate (as it isn’t an essential nutrient, the body can make it well enough), however a key indicator of individual requirement would be milk supply for the breastfeeding mother, and mood, energy and stress response may also be good indicators. Carbohydrate helps produce serotonin in the body and quality sources such as potato or kumara can be great for helping with mood and calming anxiety. There’s no right or wrong way here, but I wouldn’t recommend a ketogenic diet for most healthy women post-birth, instead aiming for a good intake of vegetable fibre and adding a couple of serves of fruit and/or kumara or potato into the day. This may take the carbohydrate content to around 80-120g per day which is still a low-moderate amount. Quality is key here.

It is well recognised that breastfeeding increases the caloric requirements of women by around 600 per day compared to pre-pregnancy, however there are no guidelines for an increased caloric intake post-birth for women who don’t breastfeed, which may lead to some women feeling they should immediately return to pre-pregnancy food intake for fear of not being able to lose the ‘baby weight’. It is reasonable to consider that, breast feeding or not, the healing that needs to take place to recover from childbirth will require additional calories and expectations of dropping weight quickly would ideally be put on the backburner until the body is healthy enough.

From a micronutrient standpoint, there is an increased risk of anaemia with childbirth and more so with multiple c-sections. The estimated blood losses during a c-section is thought to be up to 1000ml, so it is no wonder that someone may come out depleted. And, worth mentioning, there is a clinical link between anaemia and postpartum depression, which highlights the important role of iron in the brain. In addition, the sudden drop of progesterone post-birth may create an imbalance until normal levels resume with the menstrual cycle. Coupled with fluctuating oestrogen levels, this is thought to be one of the major influences of mood and can have negative impacts. Finally, it can take time for the thyroid (which enlarges during pregnancy) to come back to normal size, and the problems this can create for thyroid function, triggering hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism in the short term, leading to a low mood state. Therefore, along with iron, iodine, selenium, zinc and other cofactors in thyroid metabolism need to be considered.

Practically speaking, what steps should be taken to avoid post-natal depletion and adjust to the new additions to the family? Some tips from Lily Nichols:

Ideally, if possible, get strong and fit in a safe way, enlisting the help of a qualified fitness professional before and during pregnancy

While pregnant, once a week, for several weeks, purposely cook a meal to freeze for post-birth, and make sure it’s something you are going to want to eat. Casseroles, slow cooker, mince-meals, pre-cooked chicken breasts, frittatas are all things that can be frozen but if you don’t like the idea of thawing and eating these, then it’s not going to be worth making them. You may want to do this in the second trimester-beginning of third trimester, so you are sorted prior to the last few weeks when fatigue more rapidly sets in. This might require more freezer space, but this will help emulate the traditional ‘village’ feel of not having to do everything yourself post-birth. In addition, baking low sugar muffins, loaves and breads (if you’re a baker) and slicing and freezing will give something quick to consume when necessary, without you having to rely on processed refined foods. If budget allows, consider Plate Me Up, Jess’ Underground Kitchen or another company that creates prepared whole food meals to take the pressure off having to cook (and the temptation to buy take aways).

Post-birth: continue taking pre-natal supplements and look to get your nutrient blood markers taken perhaps 10-12 weeks post-birth, when inflammation and hormones that are disrupted during the pregnancy and birth have had time to settle down. This will give you a more accurate reflection of any nutrients that you may be running low in. Work with a health professional such as a nutritionist, naturopath or dietitian to provide you with good advice around quality supplements, as price of supplements don’t necessarily reflect quality.

Ensure adequate protein and fats at each meal, with a moderate amount of carbohydrate. If possible, avoid meals that are too skewed towards carbohydrate as these are going to cause blood sugar swings that will impact on energy levels and mood state. This is obviously problematic when also sleep deprived!

Don’t ignore your hunger signals. Remember you need more calories currently, breast feeding or not. Eat until satisfied and trust your body and the signals it is giving you. Now is not the time for Isagenix or fasting. That said, aim to eat your meals within a 12h window, avoiding snacking if you get up to feed during the night if possible. This is reasonable given what we know about circadian rhythm and the potential deleterious effect of food intake later in the evening.

Liver, eggs, salmon, sardines and red meat that is close to the bone all contain essential amino acids and fatty acids that are important not only for baby’s growth and development, but for mum’s brain and blood sugar. Regular inclusion of these should be a priority for optimal nutrient intake.

Keep well hydrated and electrolytes up – a major source of fatigue is when plasma volume drops due to dehydration, therefore making the blood more viscous and increasing the work the heart has to do to pump it around the body.

PC: home-startcentralbeds.org.uk