Don’t confuse ambition with ability. This is a standard Mark Watson quote on Radio Sport that he regularly pulls out when describing athletes who mistakenly assume they are more skilled, fitter or more able than they actually are. This confidence is a necessary part of being an athlete and, indeed, I’d be a far better athlete if I backed myself a bit more.* However there are times and situations where your physical and mental skills are not enough to overcome the challenge at hand. This time of year is a perfect example of where many people have the best of intentions of eating well (ambition), yet put themselves in the position where they are without the physiological components necessary to do it (ability). They struggle to make good food choices as their job necessitates nights out with clients, lunch meetings that involve alcohol, and one function after another. On top of that, every body feels the need to catch up before Christmas – almost like the 25th December is D-day and it’s an absolute impossibility for any of these catch-ups to take place after the presents have been opened. The additional commitments are on an already tight schedule can lead to people relying on increased amounts of caffeine, cortisol and too little sleep in an effort to fit everything in before the Christmas break. When this is combined with fruit cake, mince tarts and an endless supply of Miami wine cooler, it’s no wonder numbers such as ‘5kg’ are bandied about as the expected weight gain.

One common strategy to navigate the Christmas cheer is to drastically cut calories consumed at meals and ramp up energy burnt through exercise to offset the increased intake of Christmas treats. Hunger usually prevails though and, come that afternoon Christmas tea shout, the one fruit mince pie that has been ‘earned’ by not eating breakfast quickly turns into four, along with crackers, Christmas nuts and three chocolate Santas to round off what has turned into an afternoon sugar binge. Throw in a healthy amount of self-admonishment that they’ve been weak in the face of temptation, people often arrive at my clinic already defeated by the prospect of December, and the calendar has barely ticked over to the new month.

The first mistake is that people see themselves as the Master of their Own Destiny – like they are in complete control of their food choices and should be strong (or will be weak) according to their willpower. If people believe they don’t have enough willpower to withstand the temptation around them, it’s more likely they’ll decide to forgo any plans to eat well until New Years, when they draw a line in the sand and ‘start again.’ It’s true that your ability to have just two bites of the Christmas cake (and not two pieces) is down to willpower – however, many people don’t know that self-control (or willpower) is a limited resource. If you’ve exerted self-control in one situation (food related or not), your ability to exert yourself similarly later on in the day is compromised. This research also points to fatigue being a contributor to loss of control later on, and the factors mentioned above can certainly leave you more tired than usual. Unsurprisingly, willpower is related to blood sugar levels. Not only does willpower use up glucose in the body, once our blood sugar levels dip below normal, it’s our natural evolutionary response to seek out foods that will bring our sugar levels up – thus making those mince tarts even more appealing as a way to boost blood sugar (and energy) levels. This makes sense when you consider that the obligate fuel of the brain is glucose – and when you are running on empty in an effort to conserve calories, your limited supply of energy is quickly used up. So don’t beat yourself up about it – blame evolution!

Obviously this does nothing to solve the actual problem. The above scenario certainly is beyond your physiological control; where you can step in and make some difference is that one step before. Some level of personal responsibility will go a long way to help you avoid having to worry about self-control in the first place. And this is where you can back yourself – you have the ability to offset much of fatigue-related diet downfalls that often prevail at this time of year. What you eat really counts. Ten points I’m sure are nothing you haven’t heard before – but it’s always good to remember them:

- Eat a good amount of fat and protein in your meals. Not only will this help reduce your hunger and appetite later in the day, it will also reduce your brain’s food-reward response – especially if the carbohydrate component of your meals is comprised of low glycaemic index options. Read: step away from the box of Special K you’ve chosen for breakfast just because it boasts only 112 Calories per serve.

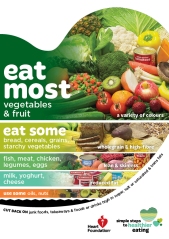

- Eat a good volume of food at each meal – include plenty of non-starchy vegetables as these will contribute to making you feel fuller and give plenty of vitamins and minerals to help keep you feeling nourished and (for want of a better word) healthy. People eat a similar amount of food regardless of where the energy comes from so (for those who look to maintain or lose a bit of weight as many clients of mine do) ensure plenty of bulk.

- Don’t confuse paleo-like treats with real food. These are still treats, despite being made with ‘clean’ ingredients. There are definitely a time and a place for them – but not every time you eat, or in place of every meal.

- Drink enough water so you don’t feel thirsty – especially before hitting after-work drinks. Too many people neck their first beer or wine because they are thirsty. Have a drink of water before ordering your first alcoholic drink. I would also advise you to drink sparkling water in between each drink – but if you are like almost anyone else I’ve ever told to do that, you’ll ignore me. So I won’t.

- Have something with a good amount of protein in it before turning up to a meal, particularly if you suspect there are going to be a lot of foods on offer that don’t align with how you normally eat. This will help you be a bit choosier than what you would otherwise, as you’re not driven by hunger.

- Choose 2-3 things to fill your plate at a gathering, rather than 5 or 6. It won’t be the last time you’ll see these foods (I promise you. In fact, you will likely be offered that same sausage roll again next week. If you so desire you can have it then).

- Step away from the buffet table. This will offset a lot of mindless picking that occurs when you’re close to a table of food.

- Have a tablespoon of raw apple cider vinegar before meal times to help support digestion and promote good gut health – essential for overall immune function, particularly if you’re running low of sleep and high on stress.

- Get enough sleep. Really try to. This will help you offset fatigue caused by lack of sleep, thus helping maintain your ability to make decisions and regulate self-control and willpower.

- Exercise. Don’t forgo your normal exercise pattern because you’re running low on time. Make it a priority. Equally, though, don’t offset those 4 glasses of champagne by an additional 60 minutes on the cross trainer. That’ll only work to drain any ability to withstand the call of the vending machine in the afternoon. Be sensible. Move more during the day where you can in everyday life, and work a bit harder in the time you already spend exercising instead of being mental about it.

Most importantly – think about why you want to eat healthy in the first instance. Often times instant gratification wins out over long term goals for health and wellbeing. And that’s fine – but if that happens then own it, accept it, and move on. Don’t beat yourself up about it, as treats are just that – to be enjoyed. Otherwise, what’s the point? You will though feel so much better if you mindfully choose times where you let you hair down, rather than feel you’ve got no willpower. Take steps necessary to ensure you’ve not confused ambition with ability – that in fact you have the ability to eat well, feel good over the holiday period and really enjoy it.

* Possibly more training and probably more natural talent would also make me a better athlete.